In recent years, Uzbekistan has launched an ambitious tourism drive that is rapidly transforming the country. Yet, at the heart of this change lies a breathtaking and largely hidden valley.

At dawn in Tashkent, a massive Soviet-era train creaks into the station and comes to a stop. I’ve taken several packed trains across Uzbekistan, but this one—heading east to the city of Margilan, the gateway to the Fergana Valley—is noticeably absent of foreign tourists.

Inside, I find myself seated next to a family of three. The mother, Gulnora, wears a vibrant headscarf adorned with bold geometric patterns. I point to it and say, “Ajoyib!”—Uzbek for “wonderful.” She smiles warmly and tells me she got it from the valley we’re traveling to.

Just the day before, while wandering through Tashkent’s blue-domed Chorsu Bazaar—one of the oldest markets in Central Asia—I had stumbled upon a mound of strawberries. Though tiny, they were bursting with flavor, like the essence of spring. Using Google Translate, I asked the vendor where they were grown. Without hesitation, he replied, “Fergana.”

Back on the train, I offer the last of my strawberries to the family. Gulnora beams and responds by opening her own container, revealing a colorful array of fresh and dried fruits—mulberries, apricots, apples, oranges, and strawberries—all from the Fergana Valley. She then takes out a small ceramic plate and lovingly arranges a little feast for us to share.

Nestled between the Tien Shan and Alay mountain ranges, the Fergana Valley spans eastern Uzbekistan, southern Kyrgyzstan, and northern Tajikistan. This lush intermountain basin—nourished by the Naryn and Kara Darya rivers—is among Central Asia’s most fertile regions, sustaining both agriculture and culture for centuries. It’s also the birthplace of Uzbekistan’s famed silk, ceramics, and fruit production—a trio that remains central to the country’s cultural identity.

Historically, the Fergana Valley, like much of present-day Uzbekistan, lay along the legendary Silk Road. For centuries, it served as a vital link for trade, ideas, and craftsmanship between China, Persia, and the Mediterranean. In recent years, Uzbekistan has embraced its Silk Road heritage with a bold push to boost tourism. Cities like Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva—once bustling trade hubs—are now developing rapidly.

Eased visa policies, improved flight connectivity, and the launch of the country’s first major international biennial have helped draw more global attention. However, some critics warn that the country’s glossy recreations of its cultural traditions risk turning it into a Silk Road theme park.Beyond Uzbekistan’s polished resorts and imitation “ethnographic parks,” a quieter, more authentic cultural revival is taking place in the Fergana Valley. While this traditional heartland of Uzbek heritage attracts far fewer tourists than the country’s major cities, it remains a vibrant, living showcase of craftsmanship.

In Margilan, one of the valley’s oldest cities, ikat textiles are still woven by hand and worn throughout Uzbekistan as skullcaps, scarves, and stylish modern clothing. In nearby Rishtan, distinctive ceramics continue to grace dining tables across the nation, used to serve meals and tea. And the valley’s abundant fruit plays a central role in Uzbek hospitality—dried apricots and raisins are offered with tea, while pomegranates and cherries are often mixed into plov, the beloved national dish.

Placing my hand over my heart—a traditional Uzbek gesture of gratitude—I thank Gulnora for her warm company on the train and step off in Margilan to find my guesthouse. Fittingly named Ikathouse, the space is adorned with wooden divans draped in colorful, handwoven ikat fabrics. I soon discover it belongs to the family of Rasuljon Mirzaahmedov, a fifth-generation ikat master who has worked with designer Oscar de la Renta to produce a collection featuring Fergana’s iconic weaves: adras (a cotton-silk blend), atlas (satin ikat), and baghmal (velvet ikat).

Margilan is the cradle of Uzbek ikat—one of the most intricate textile traditions in Central Asia. Known locally as abrbandi, this silk-weaving craft dates back over a millennium and was traded along the Silk Road as early as the 11th century. Although ikat weaving arrived in Uzbekistan after the Arab Conquest in the 7th century, legend tells of an even earlier connection: a Chinese princess is said to have smuggled silkworm eggs in her hair to the Fergana Valley in the 4th century when she eloped—sparking Uzbekistan’s centuries-long romance with silk. Remarkably, in Margilan, the painstaking weaving process is still carried out entirely by hand.

At Yodgorlik, one of the city’s oldest and most revered silk factories, silkworms quietly feed on fresh mulberry leaves until they grow large enough to spin their delicate cocoons. “We only use cocoons that the larvae have naturally vacated,” says Luiza Kamolova, Yodgorlik’s director. “If we destroy the larvae, we destroy the future of Uzbek silk.”

The harvested silk is washed, stretched, and bundled into skeins, then dyed through a labor-intensive resist-dyeing process using natural pigments—yellow from onion skins, red from madder roots, blue from indigo leaves, and brown from pomegranate rinds. Artisans labor over steaming vats, coaxing colors into the threads. The final result is a soft, feathered blur of color and pattern—woven into fabric that is cherished across Uzbekistan in both traditional garments and modern fashion.

“When you think of Uzbek ikat, you think of the Fergana Valley,” says Charos Kamalova, founder of Teplo, a Tashkent-based marketplace spotlighting designers from all over the country. “Every designer working with traditional fabrics sources material from this region—it’s simply a given.”

At the Yodgorlik workshop, a blue-and-white silk scarf flutters in the courtyard breeze. “Its colors are inspired by Rishtan ceramics,” an artisan tells me. “Have you been there yet?”

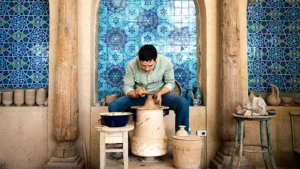

Two days later, I arrive in Rishtan, greeted by a towering ceramic pot at the center of a roundabout. Locals say the sculpture pays homage to a traditional four-handled pitcher known as bodiya chuqur bodiya, used throughout Uzbekistan for boiling water to make tea. At Koron, a nearby ceramics gallery, I browse through rows of colorful pottery—bowls, jugs, tiles, and pomegranates of every size and shade. “The pomegranate is sacred in Uzbek culture,” says Ravshan Tojiddinov, the gallery’s founder. “We give it at weddings for fertility, paint it on ceramics for good luck, and eat it to remind ourselves that life is both sweet and sharp.”

Later, I visit the workshop of Rustam Usmanov—one of Uzbekistan’s most esteemed ceramicists. Part studio, part school, the space buzzes with students sketching designs beside shelves stacked with half-finished pottery. “The clay we use here in Rishtan has a natural reddish-yellow tint,” Usmanov explains. “The entire city is, quite literally, built on it.” This local clay is shaped and dried for up to ten days, then coated with white clay before being fired at 920°C. Delicate, plant-inspired patterns are painted by hand before a second firing at 960–1000°C seals the alkaline glaze, revealing the vivid blue hues that define traditional Uzbek ceramics.

“Every Rishtan ceramic tells a story,” one of Usmanov’s students shares with me. “Birds symbolize freedom, fruits represent abundance, and the jug—whether for water, milk, or wine—embodies life itself. These aren’t just decorations; they’re blessings brought into the Uzbek home.”

While I’m photographing a ripening pomegranate hanging from a tree in the courtyard of Usmanov’s workshop, he notices and offers me a handful of dried apricots, walnuts, and apples. As he does, he echoes what Gulnora and many others have told me—that the nearby city of Fergana is home to some of the finest fruit in the country.

When I step out of a marshrutka (shared minibus) in Fergana, the valley’s namesake city, I’m immediately surrounded by fruit trees. Grapevines sprawl over mudbrick homes, cherries dangle from low-hanging branches, and apricot trees bloom in almost every courtyard. On street corners, I see locals rinsing strawberries in shared water basins, children chasing plums rolling down alleyways, and elderly women shaking mulberry trees to gather fruit for jam.

At the local farmer’s market, the scene is nothing short of dazzling: sun-kissed peaches lined up in neat rows, pyramids of crisp apples, bunches of heavy purple grapes, and baskets of strawberries so fragrant they scent the entire air. “Everything here was picked just this morning,” a vendor tells me. “We grow first for our families, then for the market—and only after that, whatever’s left goes for export.”